Captain Sobel was a demanding, motivated company commander who was in the right place and time to forge one of the finest companies in the U.S. Army -- he was also truly hated by his men and officers for being petty, arbitrary, and (unforgivably) his lack of judgment. Then a subordinate and later the company commander, Dick Winters saw it as a result of Sobel's rash decision making -- acting without reflection or consultation. A near mutiny while the company was in England that finally resulted in Sobel losing his company. This conflict is at the core of the first part of Stephen Ambrose's book Band of Brothers.

Whether you teach, lead, or command make sure your followers know what they're supposed to do before they're supposed to do it.

But no amount of trust, or fear, will make people do what they don't know how to do.

Teaching people how to do things is relatively easy, and a personality like Sobel's can, by threat of punishment, force people to practice manual skills and simple yes/no decision making to achieve higher proficiency. The quality of Easy Company's initial training allowed them to do it better then most, and established a esprit de corps that kept passing down solid training and high expectations as replacements continually came into the unit once they entered combat.

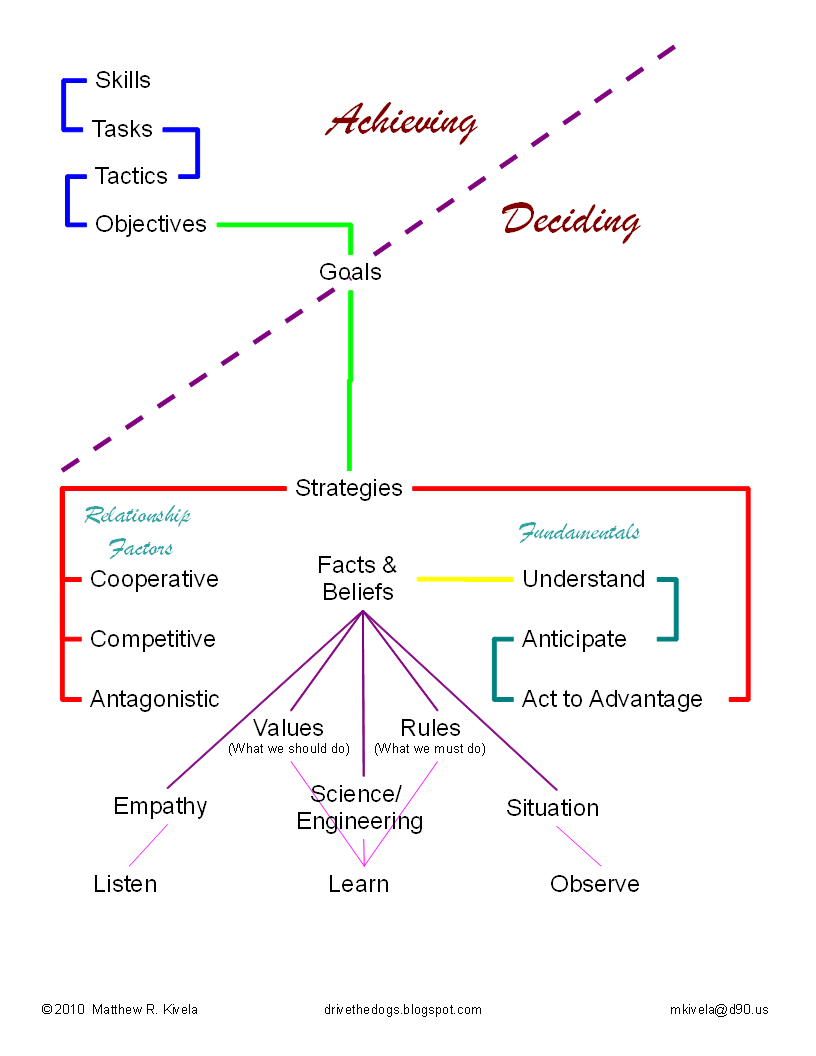

True leadership requires developing the trust of the subordinates (as well as superiors) that replaces fear of failure with confidence to follow orders. Much of this blog will focus on this trust building side -- particularly how to determine and articulate the right goals -- but some housekeeping is first in order to provide some definitions for the "achieving" side of the diagram

Skills are discrete items, as is information. Being able to read is a skill, which is much handier when you have information that tells you the hours and location of the library.

Tasks are steps of a bigger plan accomplished by skills. Reading and highlighting a specific book is a task.

Tactics are a set of tasks that accomplish an objective. Studying is a tactic to pass a test -- it uses many tasks (read several books, review notes, attend study group, etc). Cheating would be a different tactic. Altering the test is another, albeit rare, tactic (see KOBAYASHI MARU...James T. Kirk solution).

An Objective is a measurable, significant accomplishment. Passing or failing a class is measurable and significant. Parts of an objective, such as passing individual tests in a course, are milestones -- they measure your progress towards the objective and give you the opportunity to adjust.

Make sure the skills, competency with tasks, and understanding of tactics is in place before you ask people to achieve the objectives you've set; and make sure you measure your progress towards those goals so you can take corrective action before you miss an objective.

Sobel was able to get his men to be capable of greatness, but it took someone else to lead them there.